The Threat of Spring Starving Bees

It’s March 27. And I am worried about starving bees.

This may come as a surprise to you, given I am in Texas. If I look around, much that was brown, dry, and dormant two months ago is now green and alive. For weeks wildflowers have started to appear across the landscape. But high on my list of concerns as I do inspections is checking for hives on the verge of starvation.

It’s worth noting that there is nothing unique about this year that has brought about this concern. In fact, we’ve had a really nice spring that is conducive to a good nectar flow: no late freezes and lots of rain (but enough sunny periods in between bouts of storms that mean flowers can replenish nectar if they are producing it!). Starving bees in March in Texas and other parts of the South is, in fact, a very common occurrence. Let’s dive into why:

We are sitting in this awkward period where colony populations have exploded, yet we are still weeks away from a nectar flow here in Central Texas. Early pollen flows starting in February have resulted in colonies bursting with brood and emerging bees. But honey bees are still living off of last year’s honey supply. The last time our bees had a nectar flow was October-more than five months ago!

And this is not unique to Central Texas: most areas that don’t provide for nectar year round are going to have a period in which colonies are growing rapidly, but enough nectar is not yet available to sustain the growing colony. So if you are in East Texas, this potential starvation period is likely a few weeks ahead of us here in Central Texas, because in general bees East of us are a bit ahead of our schedule. The fact is, the weeks ahead of the major nectar flow in most areas tends to produce this concerning set of circumstances.

There’s a good reason for this early build up of the bee population ahead of a nectar flow: a colony wants the largest population possible to gather nectar once the flow starts. This ensures the colony has enough honey stores to last until the next nectar flow. A smaller population would be unable to gather as much nectar as a larger population, so that early pollen availability provides the protein needed to start early brood rearing to ensure these bees can mature into adults, and eventually into foraging bees, ahead of the nectar flow.

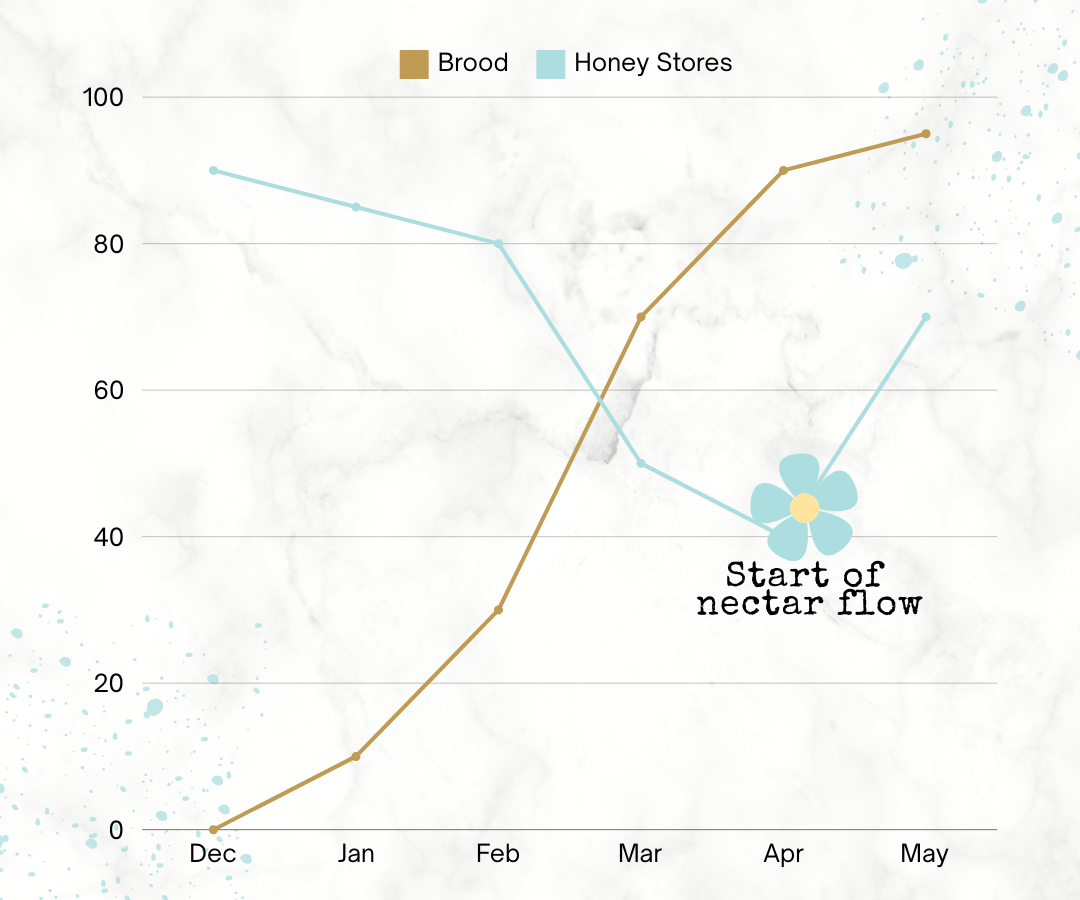

In the very unscientific chart shown above, you can see that colony expansion happens in the weeks (or even months) ahead of the nectar flow, creating more mouths to feed and a situation where bees are at risk of running out of stored honey ahead of when the nectar flow begins.

So while we are watching closely for swarming bees, we are also assessing food stores very carefully. If your strongest colonies do not have at least 3-4 frames of stored nectar or honey, I would consider feeding a few quarts of sugar syrup each week or share resources from another hive. Note that pollen scarcity is generally not an issue, but if so you may also need to consider pollen substitutes. We are not seeing any pollen scarcity in Central Texas right now (and rarely do this time of year.) Remember: pollen does NOT equal nectar. Pollen will not sustain your adult population, so seeing evidence of pollen does not mean your colony is well fed. Only nectar and honey can provide the carbohydrates needed to sustain adult honey bees.

Each year during March I encounter at least one beekeeper whose colony starves to death, because they assume that flowering blooms and a green landscape means bees are well fed! Please make sure you are assessing stores in your colonies each time you inspect, but in particular ahead of your strongest nectar flow: remember that this is a time when a growing colony may have access to little or no carbohydrates stores!

Leave a Reply