Winter is Coming

Steps to Take to Help Ensure Your Colonies are Set up for Winter Success

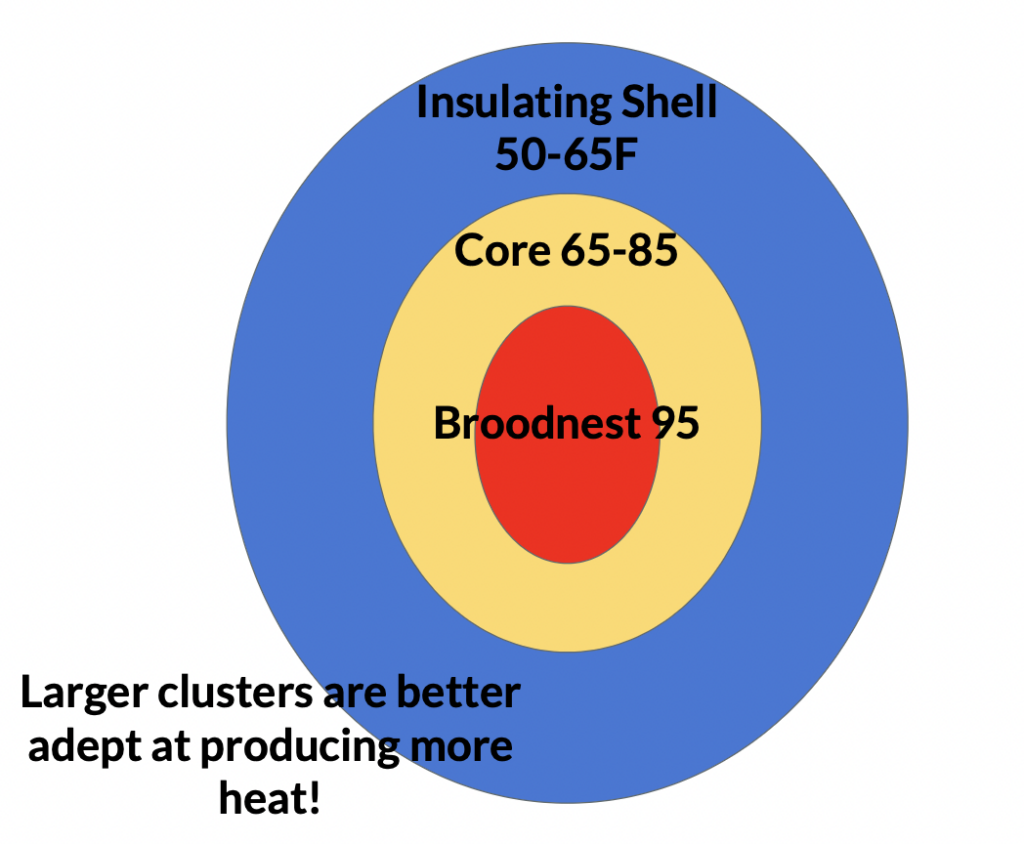

It’s October 20 in Texas and though it’s going to be 86°F today, my beekeepers are out preparing hives for winter. It’s hard to think about ‘winter’ when it’s this warm out, but it is coming. The average high temperature in October for Austin is 82° and the average low is 60°. Even with our record breaking (and unrelenting) heat this year, we have seen a few nights in the 40s in the last week and temperatures should continue to drop. Though our winters are very mild compared to many others, here in Central Texas we do experience cold enough winters that our bees are forced to cluster to stay warm as a unit. When the outside temperature drops below 55°, a colony will form a tight cluster. The temperature of the core of the cluster is 95°, while the bulk of the cluster ideally needs to stay above 80°. The outermost edge of the cluster may be as low as 50°. The graphic below demonstrates the layers of a cluster and its corresponding temperatures.

A colony generally needs four things to successfully overwinter::

- Adequate carbohydrates (honey, nectar) to survive until the spring months

- A population that is disease free and strong enough so that the the colony can huddle together and keep the core of the cluster above 80°

- A proper cavity to house the colony to assist the cluster in keeping warm

- Be void of moisture

Let’s explore each of these a bit further and what a beekeeper can do/not do to set up a colony for success. Our winter prep is definitely different from that of beekeepers in the cold North, but we do need to take precautions to assist a colony’s cluster to retain heat, unlike our beekeeping friends in tropical climates.

- Adequate carbohydrates: The overwhelming majority of the nutritional needs of a colony in the winter are carbohydrates found in nectar and honey. This is the primary diet of adult honey bees. Pollen is important to a colony, but because brood rearing slows or ceases altogether during the cold months it’s not near as important. (In fact, I strongly recommend you avoid feeding pollen during the coldest months. Brood breaks are very healthy for a hive and when the hive is in a cluster they cannot keep brood alive that falls outside of the cluster.) How much honey your colony will need depends on the size of the colony and how long your winters last. If your colonies will spend many months in temperatures below freezing, your colony requires more food than ours here in Central Texas. Our colonies often have access to at least some nectar starting in March, and even if they don’t temperatures are warm enough that we can begin to feed sugar syrup. Also, larger colonies will need more food stores than smaller colonies. If you are in Texas, I recommend leaving roughly 30 pounds of honey, at least, on all of your larger colonies. If your colonies are light, you will need to find a way to provide emergency feed. Mountain camp feeding and candy boards are both good options. Next month I will share with you how to mountain camp feed your hives, which is my preferred method for winter feeding.

- Strong and disease-free populations: A colony’s ability to stay warm is dependent on having enough bodies to generate the heat required to keep the cluster above 80°. This is another area where the recommendation diverges based on how harsh your winters are. Here in Texas, as long as we have a fairly mild winter and no extended harsh freezes (which is fairly common) I can overwinter a nuc as long as 4-5 frames are completely covered in bees. This would be a much more challenging, if not impossible, feat in a really cold climate. You can help prepare your colony for winter by combining weaker colonies with stronger colonies ahead of winter, and ensuring you are going into winter with healthy populations with low mite counts.

- Proper cavity: If you have seen an ‘open-air’ colony– a colony in which the bees build their beeswax comb in the open and not inside of another vessel–its quite a sight to see. But it’s rare for a reason: colonies need insulation and protection from the elements. This is why it’s so common to find colonies in the wild inside of tree trunks with very small entrances–the trunk of the tree provides superior protection and insulation. Unfortunately most modern bee hives are made from pine, which does provide insulation, but not as much as some other materials. You can buy hives made from cedar and insulated plastic, which can provide more insulation, but unfortunately they are much more expensive and most of us (including me!) find ourselves with our bees in pine hives. Don’t worry–colonies can make it through winter just fine in pine hives! But if you live in the harshest of cold climates, you may find it necessary to wrap your hives or provide windbreaks to assist the colony. Here in Texas this is NOT necessary. Let me say that again for the folks in the back: Texas beekeepers DO NOT NEED TO WRAP THEIR HIVES. In fact, doing so can have negative unintended consequences because our temperatures fluctuate so much during the winter months and we have many really warm days. Your wrapped hive may actually overheat on a warm day and create a lot of excess moisture that the wrap will prevent from escaping. (More about that in a moment.) A beekeeper can assist their colonies by:

- Ensuring all gaps in woodenware are closed up (a colony should propolize these shut, but if they don’t, find a way to help them out. Extra duty duct tape works well.)

- Place your entrance reducers on the smallest entrance.

- If your colony is facing a strong cold north wind, a windbreak can help.

- Consolidate the hive down to only as much space as the colony needs to house itself. Remember, from this point forward, your colony will begin shrinking.

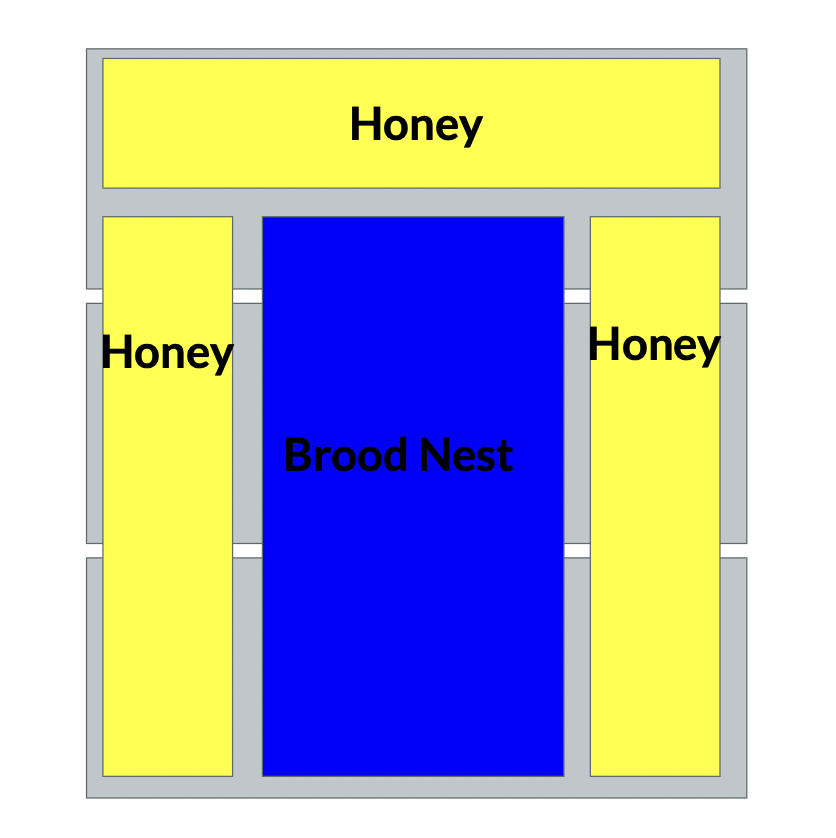

- But it is important to have empty comb in the brood nest, meaning, don’t pack the entire hive full of honey. Bees need empty comb to crawl into to keep the cluster warm.

- Finally create an “envelope” around the brood nest with the honey. Honey is a great insulator, and the cluster will move as a unit in search of food, so you want honey all around the brood nest. I’ve included a graphic below to give you an idea of what I’m talking about!

- Moisture=bad: If your colony creates a lot of moisture that cannot escape the hive, it can drip back down and freeze your bees to death. If you live in a very cold climate, this may mean you need to use a quilt board to absorb all the moisture. Here in Texas, we start to see more moisture when the temperatures rise during the day and fall again at night, usually in the early spring. Thankfully it’s generally not a concern (though you may start to see a bit of mold on your inner cover come February. If so, use a small stick or shim to ventilate your inner cover and it will clear right up. This is why wrapping your hives is ill-advised here in Texas.) You will learn in next month’s blog that a benefit to mountain camp feeding is that sugar is hygroscopic, meaning it absorbs moisture from the air, so it can also act as a force to draw moisture from a place where it can affect the colony.

And finally remember to avoid checking your hive any time temperatures are below 55°. In general, it’s a good practice to avoid checking your hives at all during a winter dearth unless you have concerns that they do not have enough food. Each time you check a hive you break its propolis seals, and the bees cannot rework the propolis to reseal a hive at lower temperatures. And of course, we never want to break a hive’s cluster. If you do, and it’s so cold that the bees cannot recluster, your colony will freeze to death.

So, start your winter preparations in the months leading up to the dearth by ensuring your bees have plenty of food stores, then after you winterize your colonies, relax! This is your off season and a time of rest for the beekeeper. It’s also a great time to reflect on the year and mentally prepare for the next. And of course, build beekeeping equipment!

Thank you so much for this interesting and timely information!

I am so glad it was helpful! -Tara